The farther upriver we went, the friendlier the natives. One day we enjoyed a northerly and sailed 60 miles. Over 100 miles up , I went ashore in a canoe and met an old man, a chief. About 40 men and 17 woman gathered there. They killed some doves and a fat dog and skinned it with shells out of the water.

The land is the finest for cultivation that I have ever set foot upon, and it abounds in trees of every description: a great many handsome oak, walnut, chestnut, yew. In addition, there is much slate and other good stone for houses. The natives are a very good people. When they supposed I was afraid, they took their arrows, broke them in pieces, and threw them into the fire. But our intentions of peace . . . our self-restraint, our tolerance of misunderstood difference, these things were not to last.

And when we failed as ship-borne explorers and discoverers, we had to turn south. Either that or dredge and then dig a trench through dry valleys to Cathay. Failures as of that moment. A botched, bungled bumping into the bankruptcy of our ideas. Bankrupted myself, as well, given the ire I face from officers of the VOC.

And as ambassadors, we didn’t manage things so well either. A few days south into our retreat from finding Cathay, we witnessed a person of the mountains jump from his canoe into the stern cabin window. As he left with clothing and bandoliers, a hot-headed member of my crew shot and killed him. This precipitated an attack by men in two canoes, one on either side. We returned fire with muskets and killed two or three of them. They continued to assault us, so we killed more of them with the cannon. And this was to be a voyage of exploration, one I imagined would result in communing with the people of Cathay. Communing, not massacring.

Near Manna-hata we anchored in a safe place. A cliff close by has a white-green color as though it were a copper or silver mine. No people there came to trouble us and we rode quietly all night, although with much wind and rain.

I confess it troubles me that our relations with the native people have not been what I imagined we’d have with those of Cathay. It troubles me even more deeply that I seem alone in my distress. I’ve seen this river leads nowhere toward Cathay; I am fearful for the path we have blazed between the Algonquins and our people.

A postscript: our ship’s Cat . . . Cathay seems to have gone missing. I loved that cat, but after searching from the bilges to the mastheads, I’m certain Cathay has not been spotted since the attacks upriver.

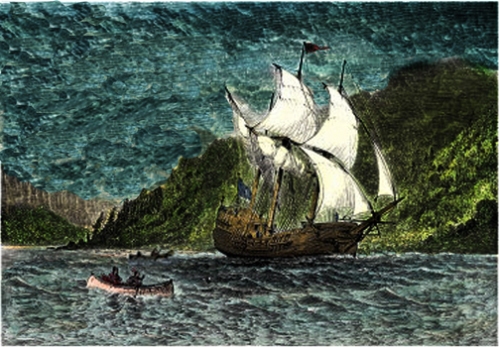

(Painting: retouched image of Sanford R. Gifford’s Sunset on the Hudson, 1876)

Yet as Mr Juet is right in saying . . . as we lay at anchor behind a sheltered sandy hook, five of our men took the ship’s boat and sailed the Narrowing of islands and into a large anchorage. As they returned, about a dozen natives in two canoes attacked the boat and with an arrow through the throat killed the leader, John Colman.

Yet as Mr Juet is right in saying . . . as we lay at anchor behind a sheltered sandy hook, five of our men took the ship’s boat and sailed the Narrowing of islands and into a large anchorage. As they returned, about a dozen natives in two canoes attacked the boat and with an arrow through the throat killed the leader, John Colman.

I, Henry Hudson, 39, have returned from my second unsuccessful voyage to Cathay. The year is 1609. I will try again working for the VOC.

I, Henry Hudson, 39, have returned from my second unsuccessful voyage to Cathay. The year is 1609. I will try again working for the VOC.